On an average day at Tenir-Koldoo, you find students hunched over their notebooks, working on their writing skills. Or they may be playing with hand puppets in the playroom, or taking shots at the goal in the small outdoor area for football and other sports. Or they may be working on a computer.

“My son is now 15 years old,” says Abdumalik. “He studies at our centre. Now he speaks well. He can write and read. He loves to play football, or he plays on the computer.”

Thanks to the centre, the students are far more independent than they might otherwise be. They can dress, do household tasks, make food, read and write and generally take care of themselves. Just as important, they are learning to express themselves through writing, art and music.

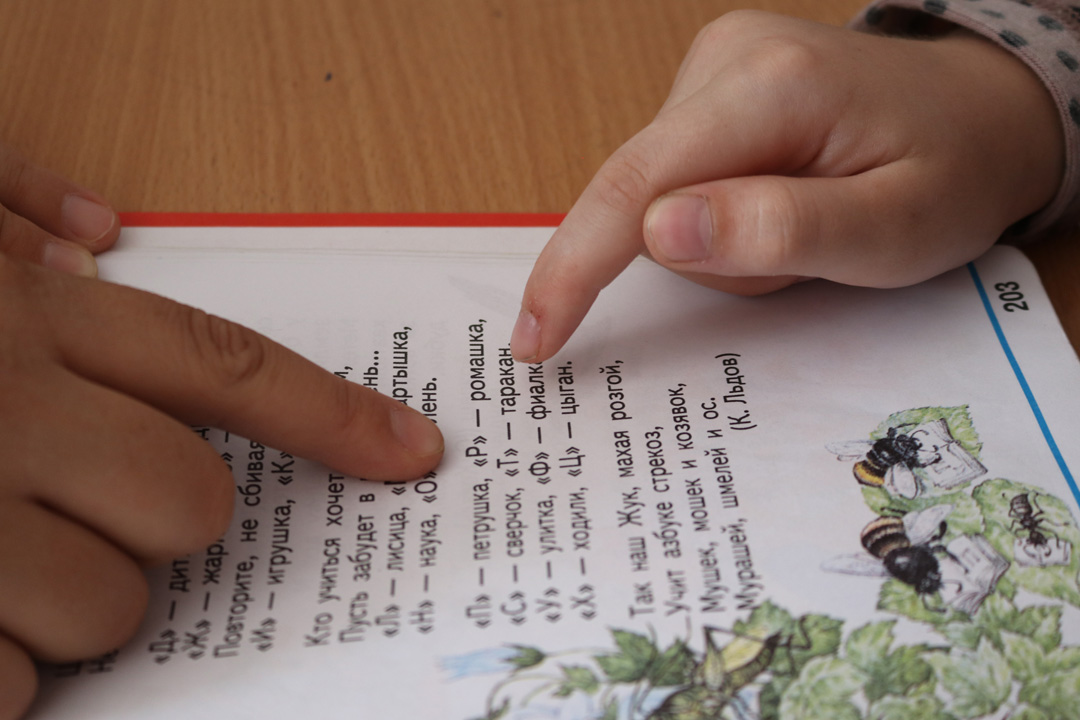

In most respects, Tenir-Koldoo is like any other small, local school. Students like 13-year-old Diana are dropped off by their parents, after which they put their coats and hats in their lockers before going off to classrooms decorated with paintings, collages, maps and blackboards.

On one recent day, Diana worked out math equations on a classroom blackboard, worked on writing assignments and made cartoon-like drawings from her own imagination. Like any good education, learning here is not just about practical, but providing the tools and skills to allow their imaginations to fully blossom.

“We came to the centre when Diana was 9 years old,” says Antonina Skorgovskaya, who works in Talas Regional Hospital and therefore could not be able to provide care, education at home. “The centre provides good support. Good training and good support. She likes to draw. She used to love drawing horses, now she draws cartoons. I haven’t seen them on TV, she takes it all out of her head.”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine