Cities are never static. They boom and bust, they grow and shrink. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, swells by some 35,000 people every month. Every year, the greater Dar es Salaam area adds the equivalent of another mid-sized city. At this rate, some predict this coastal African metropolis of 5.5 million inhabitants will be a megacity in 15 years.

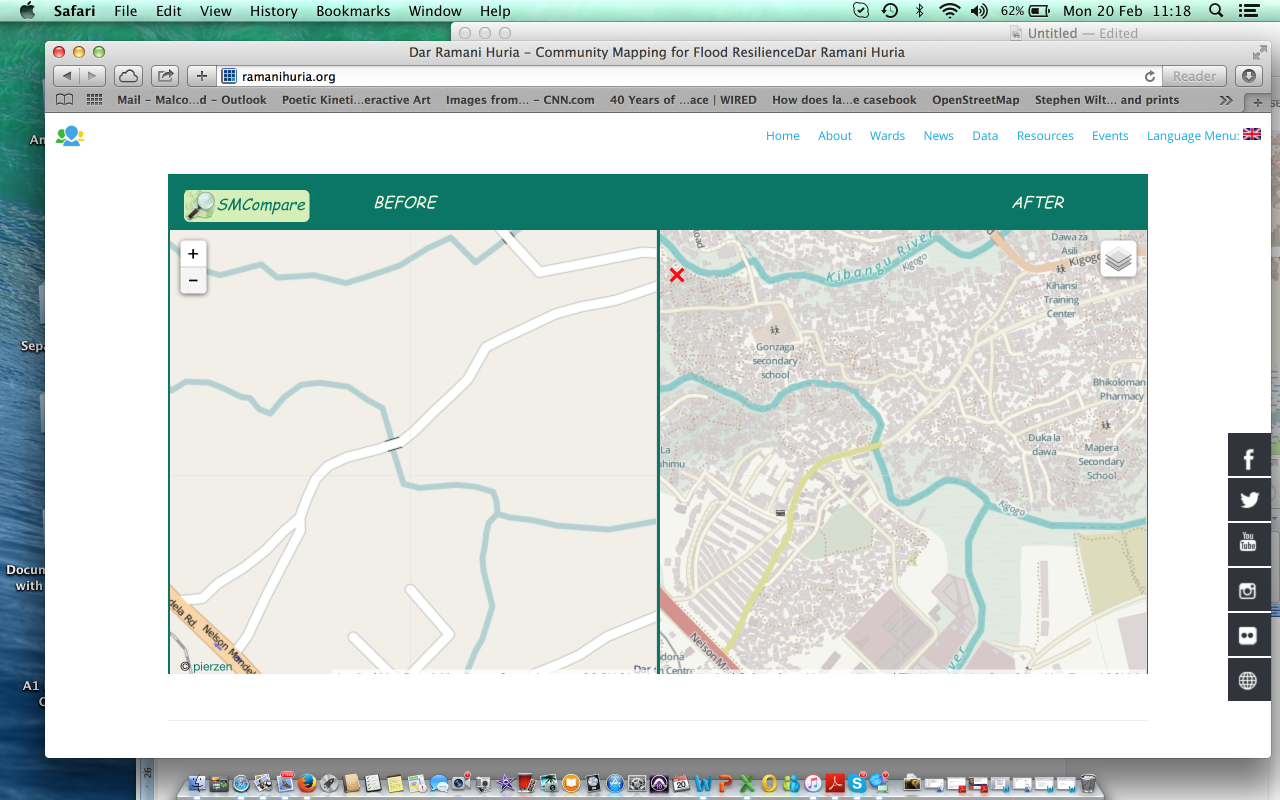

Keeping track of this growth and the changes in the cityscape is no easy task. That’s where Dar Ramani Huria comes in. A community-based mapping project that began four years ago, Dar Ramani Huria (Swahili for ‘Dar Open Map’) has brought teams of local university students together with community members to create a highly detailed atlas used by government officials and community members to improve disaster preparedness and response.

Local teams hit the streets, alleys and riverways, armed with mobile phones from which they upload GPS coordinates for local features that represent risks or that could serve as assets during an emergency, which are added to the map. The most typical urban disaster here is floods, which strike almost every rainy season. In 2011, floods claimed more than 40 lives and in 2014 another dozen were lost.

“The map has been very useful to us,” says one Red Cross volunteer who lives in Kigogo, a flood-prone and under-resourced area of Dar es Salaam. “It helps us find ways of rescuing flood victims and also knowing safe places where they can resettle temporarily. The maps can also guide people to amenities such as hospitals and schools.”

Today, highly detailed, colourful maps of 21 city wards are available for free, without restrictions, on the project’s website (ramanihuria.org). The beauty of the project, says Nyambiri Kimacha, an adviser for the Tanzania Red Cross National Society, is that the people who know and care the most about their neighbourhoods drive the process. “And they can access the map through their smartphones,” she notes. “So they can use this to identify problems so we can go work on them.”

As the maps have taken shape, they have also been used as tools for city planning and development. Mussa Natty, a city planner and member of the Kinondoni district municipal council, agrees. “It not only helps people navigate their way in a disaster, it also helps in risk-reduction measures like construction of drainage systems,” he says. “It helps us avoid hazards by understanding exactly what areas cannot be built on.

“We really needed this,” he adds. “We needed it yesterday.”

Out of time

Indeed, yesterday’s maps (pre-Ramani Huria) were badly out of date, says Mark Iliffe, a project manager for the World Bank, which supports the project, along with the American Red Cross and others. “Prior to Ramani Huria, the official maps were from 1994, when Dar es Salaam had a population of 2.5 million people,” he says. “Well it’s doubled since then. How can a town planner develop a master plan for the next 15 years when the maps don’t reflect what’s really out there?”

The beauty of online mapping is that once the community takes on the process, the maps are updated continually. The next step, says Iliffe, is to make the maps more widely available so that each neighbourhood, district and the city as a whole can advocate for solutions more effectively. Although the maps are available online and are interactive with smartphones, access to smartphones and broadband signal is not universal in Dar es Salaam. One next step therefore may be to print thousands of small neighbourhood maps that can be given out widely and regularly as information is updated.

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration