In areas affected by high levels of chronic violence in Latin America, for example, the ICRC works with National Societies and local authorities to promote behaviour among young people conducive to reducing armed violence.

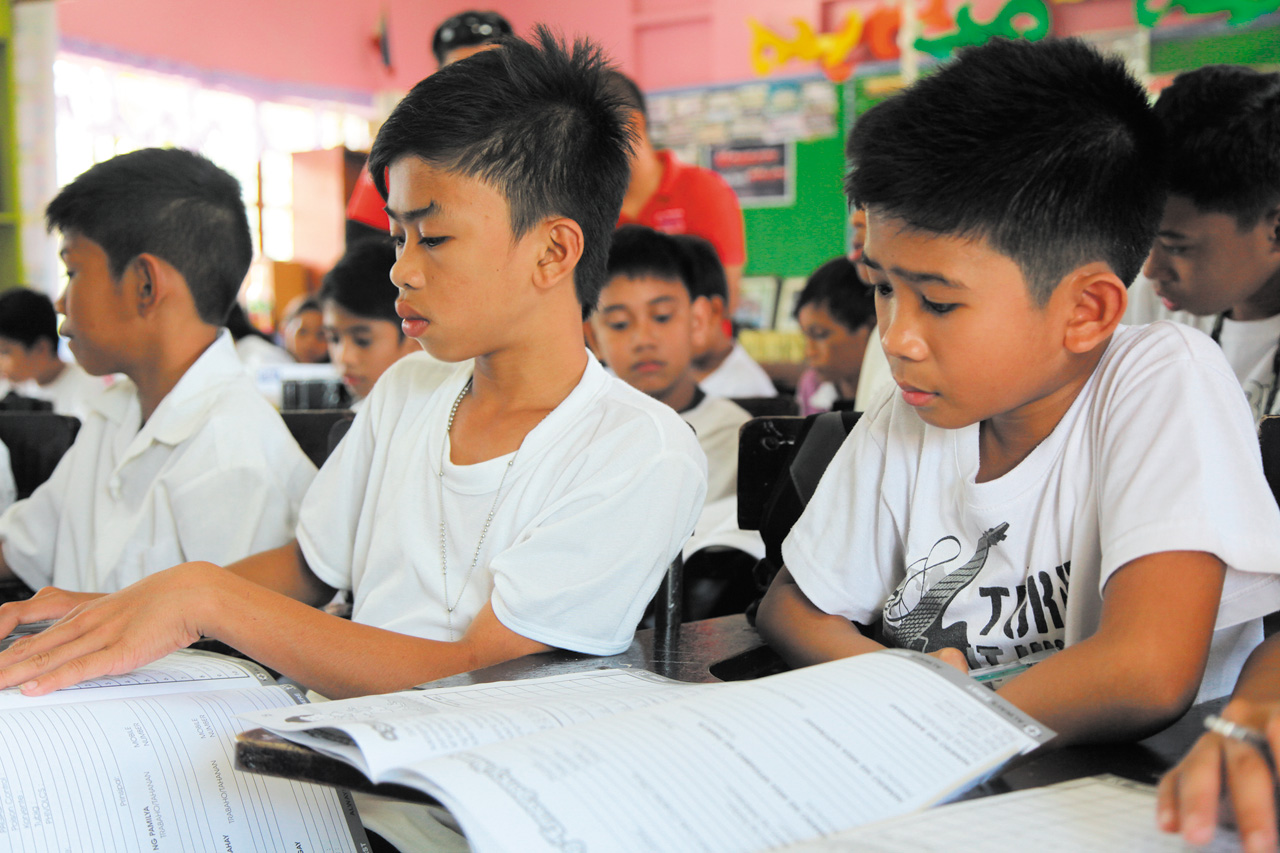

Ongoing in some 100 schools in Brazil, Colombia, Honduras and Mexico, the projects are usually linked to broader, local efforts to reduce the impact of violence, such as teaching students how to respond to violent incidents, training youth in first-aid, raising awareness of humanitarian principles and promoting safer access to healthcare.

Combined, such initiatives help provide a more learning-friendly backdrop. In the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for example, schools involved in the project reported an increased ability to hire and retain teachers, improved pupil achievement and a reduction in drop-out rates.

Filling gaps, enabling access

While none of this involves directly providing the kind of general education — reading, writing, maths, science, history, the arts — that many are calling for urgently, these initiatives do make a critical contribution.

“One thing we already do in some contexts is work to eliminate the barriers — or the gaps in protection — that get in the way of children going to school,” says Hugo van den Eertwegh, a security management and risk adviser for the ICRC.

It’s often a multi-disciplinary effort, adds Monique Nanchen, child protection adviser for the ICRC. “Our water and habitat teams, for example, work to renovate, stabilize and make school buildings safer for children,” she says. “Delegates in some cases help schools create evacuation plans and conduct drills or work with National Society volunteers or other partners to explain to students how to avoid the risks of mines or unexploded shells.”

In situations of conflict or extreme violence, the ICRC’s stance as a neutral intermediary could also play a particular role — through dialogue with armed forces, armed groups or criminal gangs — in helping to generate more respect for schools and the safety of children going to school. Meanwhile, the ICRC’s expertise on IHL allows it to call at the international level for more respect for existing international norms protecting education in situations of conflict.

Meanwhile, National Societies and the IFRC are also heavily involved in efforts to fill gaps and foster greater access to education. In numerous countries, National Societies are engaging communities in the IFRC’s Youth as Agents of Behaviour Change (YABC) curriculum, which brings young people together for peer-to-peer activities — from arts and sports to first aid — that foster non-violence and non-discrimination.

This can allow greater access to education among marginalized groups who might not otherwise feel entirely safe in school settings.

In Madagascar, for example, the Malagasy Red Cross Society is involved in the Ampinga project, which aims to combat harassment and violence, which has led to 25 per cent absentee rates in some schools. Supported by the IFRC and run in conjunction with a community group, Ampinga offers a safe space in which students can speak about acts of violence perpetrated against them or that they themselves have committed. They also confront the fear, depression and absenteeism caused by the violence and learn ways to manage anger, de-escalate tensions and promote healthier responses to disagreement and differences.

In most cases, National Societies are in the forefront of such efforts, with contributions from the ICRC, the IFRC and National Societies from elsewhere.

Since 2012, for example, the Chihuahua branch of the Mexican Red Cross has worked to foster an environment in which young people have safer access to education in Ciudad Juarez, a city on the border with the United States that has extremely high rates of violence. Supported by the ICRC and in partnership with local education authorities, the project offers non-judgemental spaces for dialogue among students — and between students and teachers — about core humanitarian values and the realities of everyday life.

In addition to practical guidance on how to deal more safely with violent episodes, psychosocial support is offered via in-school ‘helpers’ and activities such as art, sports, theatre and music.

In some crisis situations, such as refugee camps or urban areas where migrants are settling more informally, another important approach is the creation of ‘child-friendly spaces’, which give parents some assurance of security and some basic learning, social integration or psychological support. The level of education offered — usually through an external partner — varies widely, however. While children may benefit from language, art or therapeutic activities that allow them to express themselves or cope in their new situations, few of these child-friendly spaces offer anything like a comprehensive primary education.

While all these initiatives are making a difference, there is wide consensus that much more could be done through building on the Movement’s experience in developing such initiatives. But how far should Movement components go, given the scope of the tasks already at hand and the limited resources available to meet even basic physical needs?

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration