Serious but fun

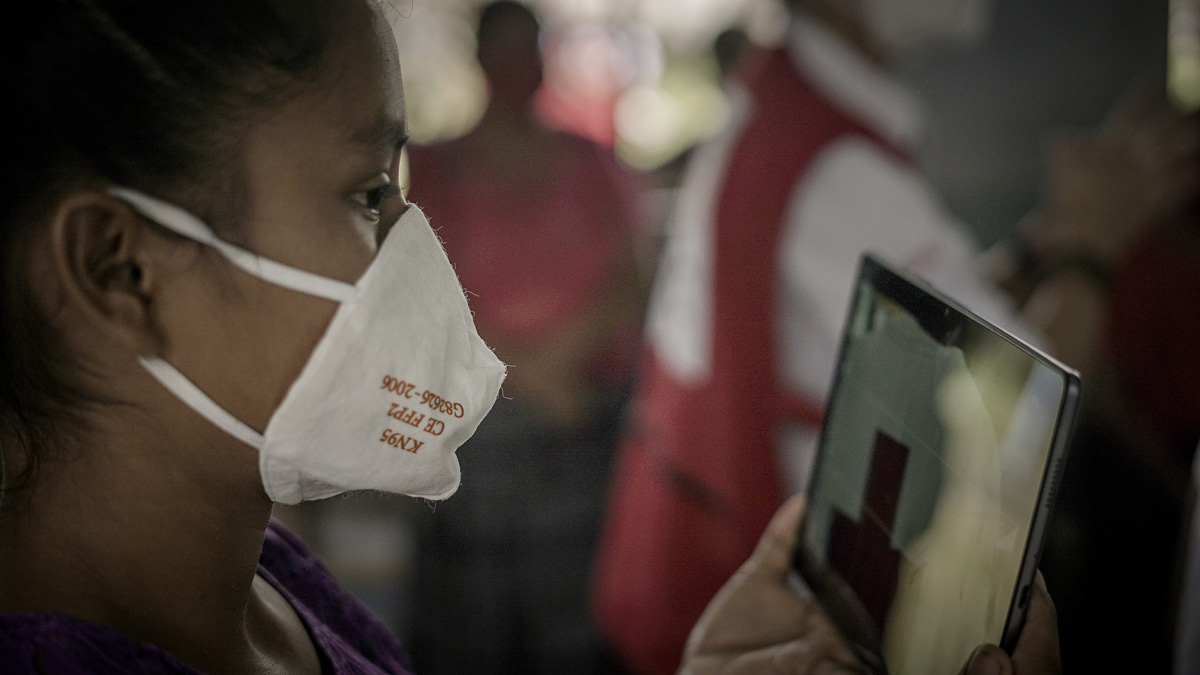

The activity began with volunteers from the GRCS working as interpreters, translating to and from Q’eqchi, the local language spoken in the community. Eventually, the community decided to be divided into 3 groups: men, women, and children. Children learned about COVID-19 and preventive measures while men and women learned about video and recording techniques.

The women’s group decided to make interviews in Spanish and Qʼeqchiʼ, making shots showing their homes and fields and how they were affected by the floods, which they called “La Llena.”

The men decided to use scripted fictional skits to address three topics: the cost of the basic shopping basket at the market and how this affects their local economy, the difficult access to health services and, finally, the problems caused by the Eta and Iota hurricanes.

For the first topic, they set up a pretend shopping scenario at a store; for the second topic they represented some health problems and how they help each other because there are no doctors nearby. For the third topic, they made videos of their crops and fields.

While the topics being raised were serious, there was also time for fun along the way. When the final videos were finally shown at a community school, children giggled and laughed as they watching their parents acting. The men and women also laughed as they watched themselves or the work of the other groups on screen.

Amid the laughter, community members shared expressions of understanding and satisfaction as they listened to each other’s testimonials, reports Carla Guananga, IFRC regional CEA specialist, who participated in the project.

“We can finally say that it is indeed possible for a community to express themselves through video even if they had never used this technology before, even if they do not speak the same language,” Guananga writes in a colorful description of the project for the platform Exposure.

The approach followed in San Luis Palo Grande illustrates the importance of putting the people at the center of humanitarian efforts, according to IFRC CEA experts. The community members were able to express themselves and communicate their needs through videos, despite the language barrier and lack of technology.

This experience showed that with the right tools and methodology, even the most remote and technologically challenged communities can have a voice and play an active role in the decision-making process during humanitarian crises.

Ultimately, it’s about the community, sharing ideas with each other, suggests Olga Marina Barrios Alvarez, community member of San Luis Palo Grande. “We are asking each other questions about each other, how we are in the village, how we got through the hurricane.”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine