With the Atlantic hurricane season already upon them, Central American relief organizations such as the Honduran Red Cross are scrambling to prepare for what will likely be a season of multi-layered disasters.

“We are preparing for population movements, dengue outbreaks, the Covid-19 pandemic, and what is predicted to be a very difficult season of tropical storms,” says Carlos Colindres, National Risk Manager of the Honduran Red Cross.

In a situation where people are already pushed to their limit, Colindres and his colleagues are working overtime to get communities ready, despite the challenges they’re already facing. “I don’t have time for anything, but I make time for everything,” he says.

One of those things is shelter. Thousands of people are still unable to return to their homes due to the damage caused by hurricanes Eta and Iota, which hit the country last November. Of the roughly 100 schools, community centres and churches used as shelters after last year’s hurricanes, six are still being used by people with nowhere else to go.

“Many people are still removing hurricane debris from their homes,” Colindres says. “We are concerned about another very active hurricane season, because there is no capacity for an extensive evacuation.”

As leader the Global Shelter Cluster (GSC) with UNHCR, the Red Cross is used to supporting and advising the government on how shelters should be managed in emergencies. But Covid-19 adds a whole new set of complications. Anti-COVID-19 measures in the shelters require rigorous respect of distancing and other protective measures, which limits capacity.

“If the evacuation centres are overcrowded, they can expose people already affected by weather events to a higher risk of COVID-19 infection,” says Roger Alonso, head of the Disaster, Climate and Crises Unit for the IFRC in the Americas. “In the confusion and chaos of the aftermath of these disasters, it’s difficult for people to maintain a safe distance and to follow the prevention guidance as much as is necessary.”

Meanwhile, interruptions of water supply and sanitation systems (in some cases caused by storm damage) can make handwashing and other basic hygiene measures far more difficult. In some areas, water blockages create favorable conditions for diseases carried by mosquitos or spread through contaminated water — all at a time when disease-tracking systems are struggling to keep up.

The government’s health system is also pushed to the limit. “It is terrible, because there are only free beds when people die,” says Colindres.

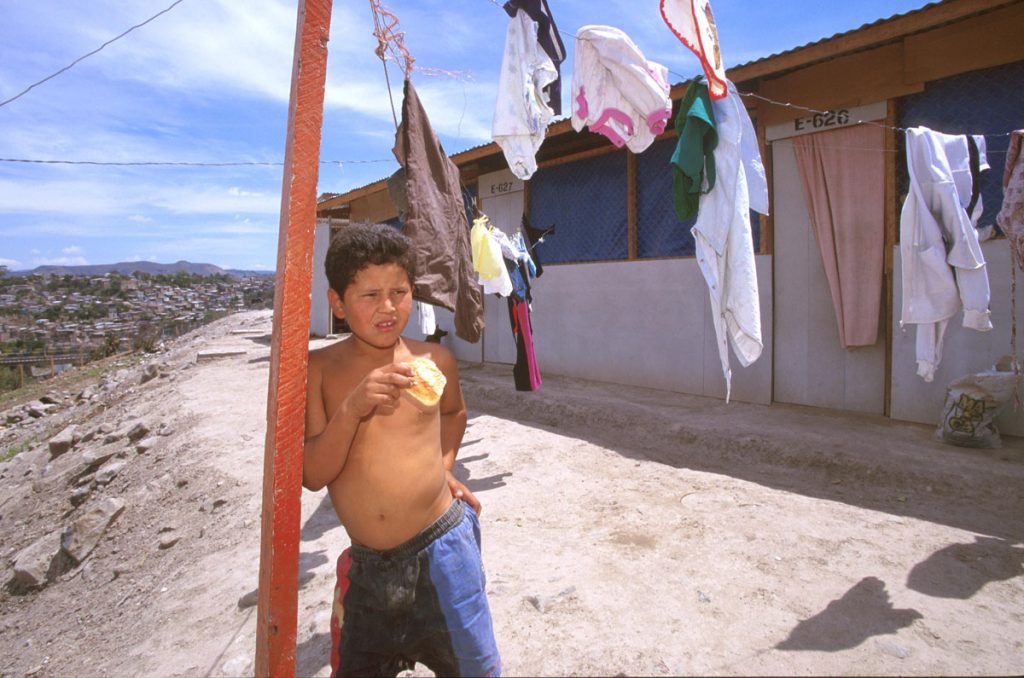

Even before the pandemic and the hurricanes, it was estimated that about 1.3 million Hondurans needed help in the areas of food security, health, protection, and water and sanitation. The near collapse of the economy due to Covid-19 has only made matters worse. “This whole situation has increased extreme poverty in the country; many people have lost their jobs”.

Meanwhile, migration through Honduras has slowed, but not stopped. “People who want to migrate do not stop because of Covid-19,” says Colindres. “They leave the country through blind spots, where there are no border controls, because many of them cannot afford to pay for the tests to enter other countries legally.”

Those who are detained and returned to the Honduran border, get assistance from the Red Cross, which provides protection, shelter, food and transportation. “The migrants come tired, they haven’t eaten or slept for a long time,” he says.

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration