A few decades ago, eye and palm scans were the stuff of high-tech thrillers and James Bond films. Today, they are a common part of daily life, even at places such camps for refugees and people displaced by crisis.

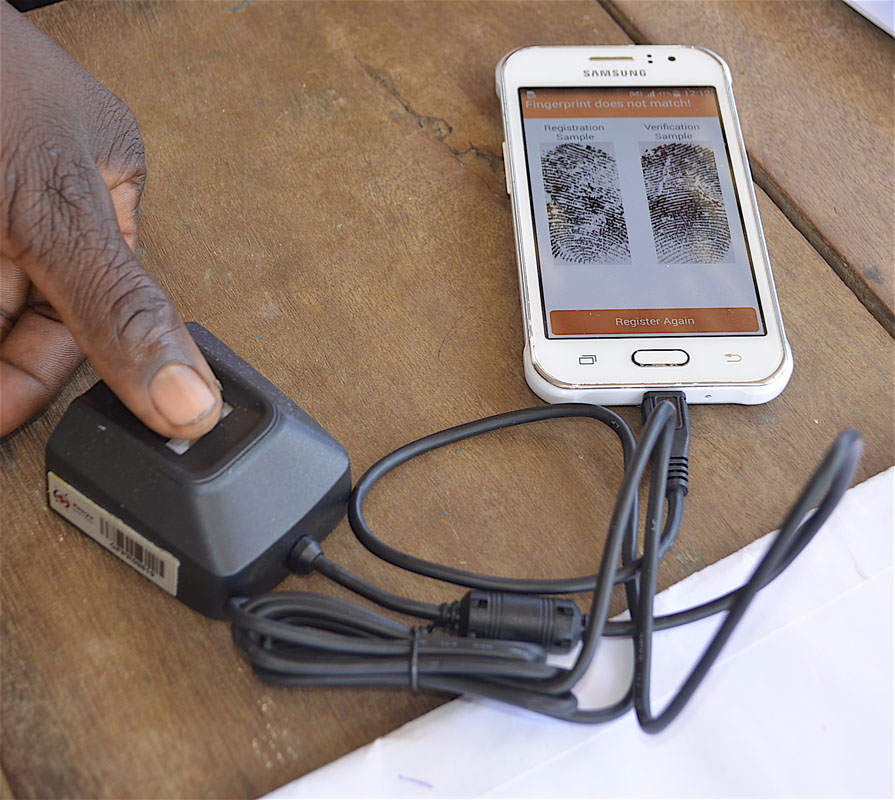

The Kenya Red Cross Society, for example, began using thumb prints and eye scans as part of its efforts to help people rebuild after devestating country-wide floods in 2018.

In the absence of clear regulations on the use of biometric data, Kenya Red Cross staff voluntarily followed the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation or GDPR as well as policies set by the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement.

“For us, it wasn’t about us coming in, doing the assessment and collecting data on the people we wanted to help,” says Steve Kenei, a data analyst for the International Centre for Humanitarian Affairs of the Kenya Red Cross Society.

“We did the assessment with the community, having them prioritize who was getting what,” he says. ”So with the biometric element, people knew with that this technology was simply further guaranteeing that the only people receiving shelter materials where those who were most in need.”

In that context, says Kinei, the use of biometric data can help build trust with communities dealing with extreme hardship. In addition, it can assure donors and the public at large by providing clearly quantifiable evidence of results.

But things like eye scans and thumb prints can also be met with skepticism and hostility from people who feel the technology is unnecessarily invasive. In recent years, refugees and displaced people in some camps have protested such practices, uncomfortable with the process and unsure how this deeply personal type of data would be used.

Part of the frustration is that people fleeing conflict, looking for shelter after violence or flooding, may not feel they are in a position to object to intrusive practices, especially if their access to food, shelter, cash or medicine depend on it.

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration