Big data

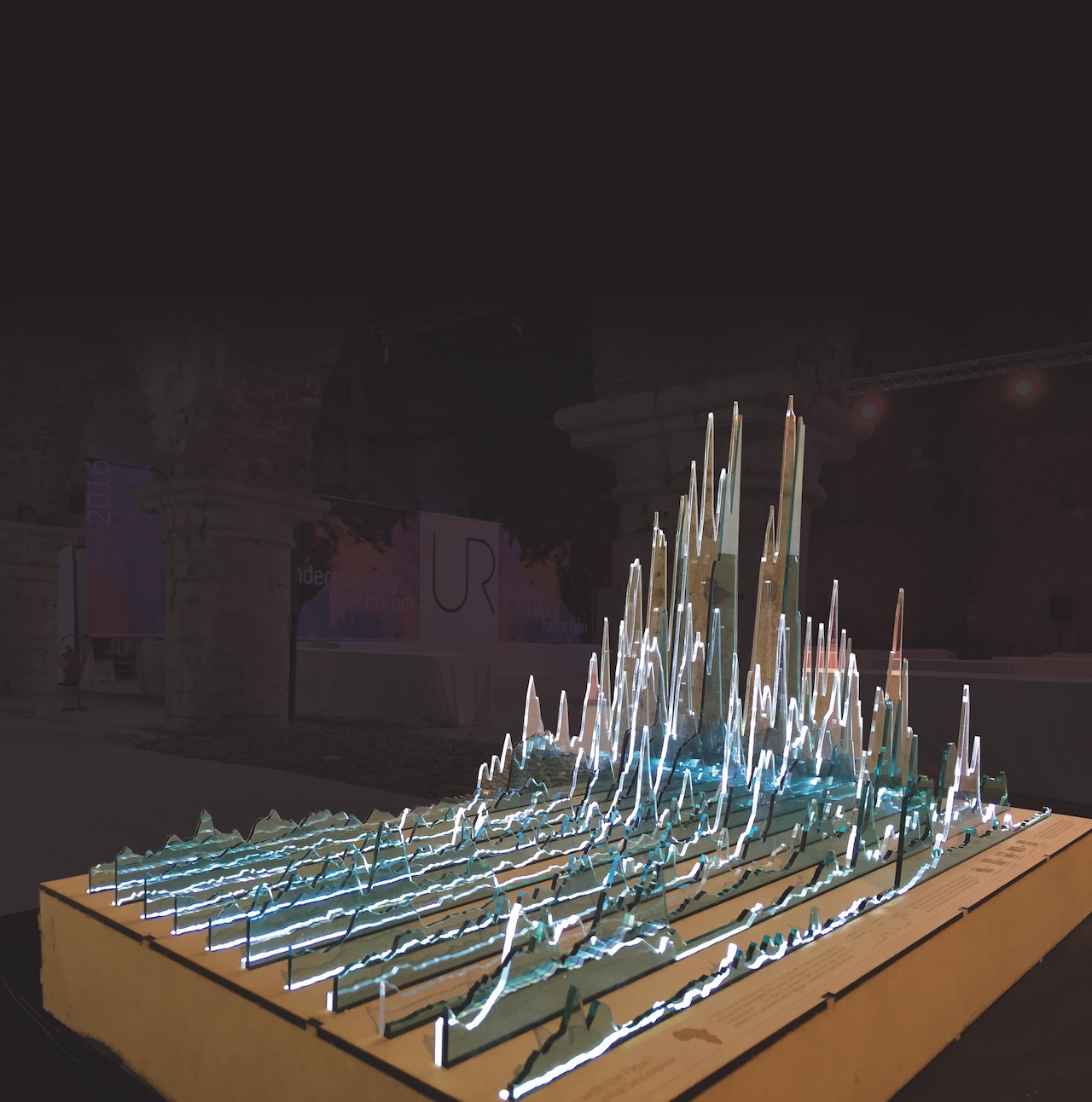

Humanitarian organizations have tended not to invest far less heavily in innovation, making use of breakthroughs developed in other sectors. But that is starting to change. How ‘big data’ is used may be one example. The Netherlands Red Cross, for example, has launched the 510 Global Initiative, which seeks to make humanitarian aid faster and more cost-effective by using machine learning to predict the damage caused by typhoons, earthquakes and floods.

“Based on historical damage data, we are increasingly able to predict the impact of a disaster, just hours after it happens,” says Maarten Van der Veen, the initiator of the project for the Netherlands Red Cross. “This initial data can help us prioritize our immediate relief operations.”

At the Nangbéto dam on the Mono River in Togo, meanwhile, machine-learning systems are helping hydropower operators predict flood risks and communicate these risks to communities downstream.

“Hydropower dams are natural partners for this initiative as it is possible to predict when flooding is likely to occur,” says Pablo Suarez, who is associate director for research and innovation at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and one of the architects behind the scheme.

After a major flood on the Mono River in 2010, when it took 34 days for disaster relief funding from international sources to reach the Togolese Red Cross, Suarez and colleagues developed a system that uses a complex algorithm to analyse past rainfall patterns and predict when the dam will reach full capacity. Disaster prevention funds are then released before any flooding takes place based on forecasts of likely peak flows downstream.

My data, my dignity

These projects are just two examples of the role data can and will play in our future. By 2018, some 3.6 billion – almost half of the world’s population – are expected to use at least one messaging app.

Humanitarian organizations are no exception. One example is ‘What now?’, an initiative supported by a partnership between Google and the IFRC’s Global Disaster Preparedness Centre, that provides worldwide mobile users with early warning and action guidance.

New research from the ICRC suggests that apps should be considered to a much greater extent as a tool to make operations more effective and responsive to rapidly evolving needs. But as the ICRC’s January 2017 report, Humanitarian Futures for Messaging Apps, points out, humanitarian organizations need to tread carefully.

Most messaging apps collect a wide range of information about users as a matter of routine business. So if humanitarians are using messaging apps to reach specific groups of people in need, they must protect that data. Even the inadvertent collection of that data could increase risks to individuals or groups.

Humanitarian organizations, therefore, must have clear and strong data-protection policies that proactively address a range of intersecting issues, from informed consent to effective encryption measures and privacy rights, among other things.

This is relevant beyond the use of messaging apps, as humanitarian organizations increasingly use electronic means to conduct field assessments, register beneficiaries and transfer funds to aid recipients. Some even use biometric data such as handprints to verify the identity of people receiving aid. This is part of the reason the ICRC recently launched a research project with Privacy International to further explore the risks of metadata generated by humanitarian organizations.

New challenges, new baggage

Indeed, with every new opportunity, trend or innovation comes a myriad of interacting technical and ethical dilemmas. The Red Cross Red Crescent Movement will need to identify, analyse and respond to these trends — and weigh in on the humanitarian consequences — more rapidly than ever.

In a recent article for the blog of the International Telecommunications Union, the ICRC’s Anja Kaspersen notes that such algorithms have diagnosed some forms of cancer more accurately than experienced human oncologists.

“And recently, an artificial intelligence algorithm called Libratus is showing great promise as a poker player,” she notes. The problem is that, so far at least, it’s hard to know why these algorithms made certain decisions and this makes corrective action or accountability extremely challenging. If artificial intelligence is used to give autonomous targeting power to weapons systems, these questions become even more serious.

“Imagine a deep learning algorithm that proves more capable than humans in distinguishing combatants from civilians,” she writes.

“Knowing it will save more civilians than human decision-makers, do we have an ethical obligation to allow this algorithm to make life-and-death decisions? Or would this be morally unacceptable, knowing that the algorithm will not be able to explain the reasoning that led to a mistake, rendering us incapable of remediating its ability to repeat that mistake?”

Understanding the potential benefits and pitfalls of artificial intelligence [AI] is critical, she says, as we appear to be “on the brink of an AI-powered global arms race… and AI-powered systems are likely to transform modern warfare as dramatically as gunpowder and nuclear arms”.

New players, new playing field

Good or bad, not all big changes affecting humanitarian action come from new technology. New humanitarian actors, including creative alliances between private, public and community actors, are changing the way people engage in humanitarian response.

“A new wave of social impact enterprises are working with NGOs [non-governmental organizations] to design solutions and attract alternate forms of financing,” says Ramya Gopalan, IFRC innovation coordinator for the Middle East and North Africa Region. “These social impact enterprises often incorporate lean, start-up management style.”

For the Movement, experience has always been one of its greatest assets. But in this new world, this can be a hindrance. “Many organizations as large as ours have an entitled approach,” Gopalan notes. “We believe we will stay in business because it’s always been that way. But that entitled approach no longer holds.”

As humanitarian organizations face more pressure from donors to transform their operating model and better coordinate their actions, including with local groups and other sectors, understanding these trends will be critical.

“The humanitarian ecosystem is screaming for change and this requires a significant mindset shift,” according to Peter Walton and Fiona Tarpey, director and manager of international strategy and policy for the Australian Red Cross, in an article for the Red Cross Red Crescent website (rcrcmagazine.org).

“We must start taking a longer-term, more systemic approach to collaboration between organizations and Movement components and find more creative coalitions,” they argue.

One example is an Australian Red Cross pilot project in Vanuatu to involve local suppliers in aid delivery. The idea is that partnerships between local suppliers, humanitarian agencies and government are formed to increase the capacity for local businesses to provide goods and services from the first rapid response. This could thereby bring relief more quickly to hard-to-reach island communities while also stimulating the local economy.

Such change will not be without pitfalls, however, and one big challenge for the Movement lies in adapting to change while ensuring respect for the values that have ensured its reputation as a trusted and neutral provider of impartial relief for more than 150 years.

“It’s not about getting rid of our traditions and our culture,” says John Sweeney, who coordinates IFRC’s futures and foresights team. “It’s about figuring out how to take on opportunities and meet the changes head on, finding things that work and scaling them up, making that the new normal and then continuing to mutate and evolve.”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration