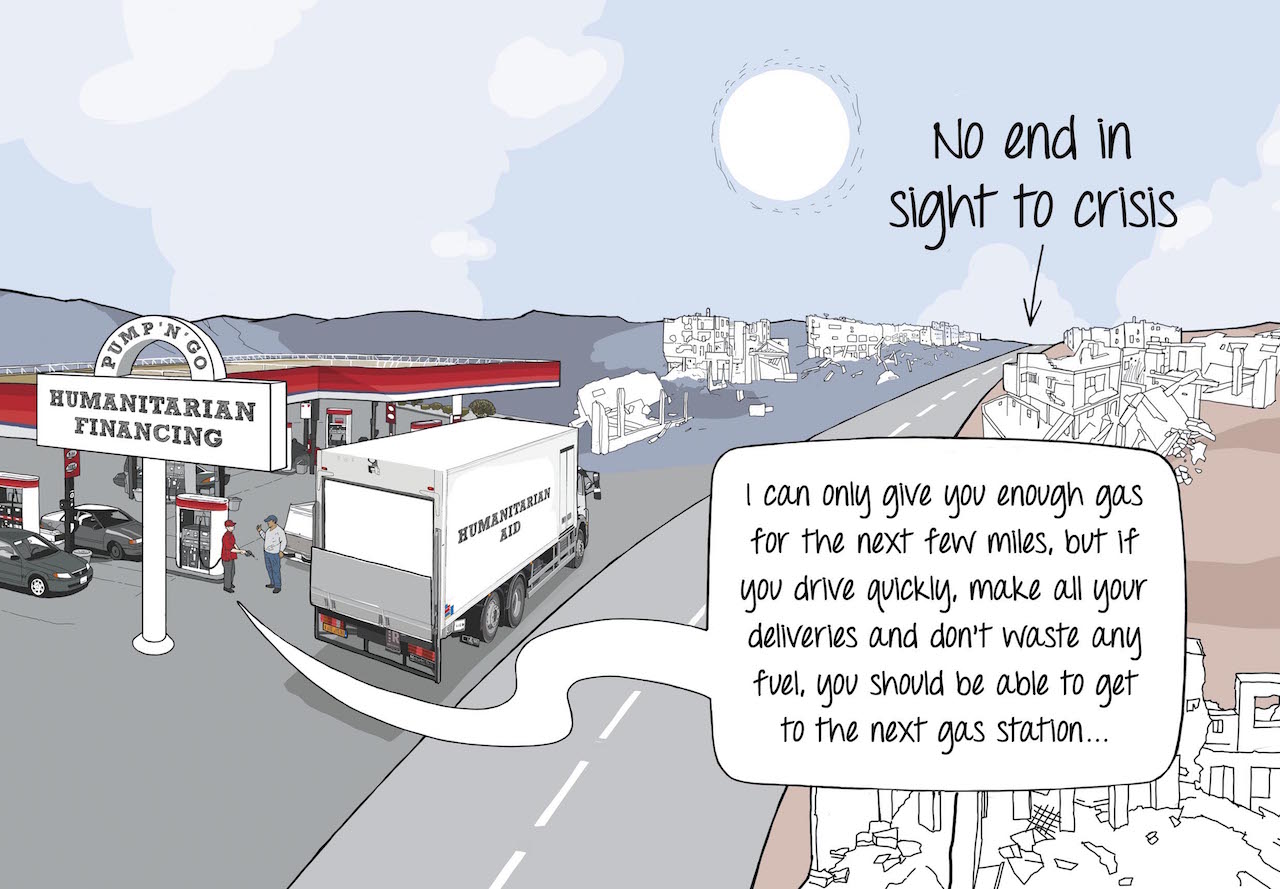

In many of today ’s emergencies, relief workers are not just saving lives. They find themselves working year after year in the same places, providing social and health services, keeping schools running, maintaining water-supply and sanitation systems and trying to find ways to help communities in war zones cope with continuous shocks.

Despite the wide range of activities humanitarian organizations undertake in today’s crises, the agencies and donors that support their work have historically made a sharp separation between what they consider to be emergency needs or long-term aid. The problem is that in today’s drawn-out crises and recurring natural disasters, ‘long term’ and ‘emergency’ increasingly overlap.

This is particularly true of the war in Syria, now in its sixth year. “It’s been a wake-up call for the humanitarian community,” says Julia Betts, an independent consultant who led a recent evaluation of Norway’s humanitarian assistance to Syria. “Protracted crises really require blended responses. The problem is that the funding streams weren’t set up for that.”

The magnitude of the Syrian crisis and the effects of refugees on host countries have created a realization about the need for combined responses that involve both humanitarian and development actors or which allow longer-term funding for humanitarian endeavours.

“At what point do you say: we accept that it is going to be like this for the next five years and we are going to adapt accordingly?” asks Betts. “That will have huge implications for staff, resources and costs.”

This is one reason that the IFRC, in response to protracted armed conflicts, climate change and major communicable disease outbreaks, has for the first time produced a five-year budget for 2016–2020. The challenge now is securing funding for that long-term emergency and development work.

Too often, says Ivana Mrdja, a senior officer in IFRC’s Partnerships and Resource Development Department in Geneva, donors still operate with humanitarian and development approaches in two very different silos. She describes the Red Cross Red Crescent’s dilemma when approaching donors for funding of health clinics, water and sanitation systems or disaster risk reduction — the whole gambit of resilience-related activities — in places where conflicts persist over years or decades.

“This is when you see the real gap,” Mrdja says, noting that for crises that are in the news, IFRC is usually able to attract funding for longer-term programmes and capacity building for National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. But in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and other situations not getting headlines, it is much more difficult.

The ‘Grand Bargain’

Could bridging the gap between humanitarian and development financing help expand the pie for these increasingly long-term humanitarian responses? The recent United Nations Report on Humanitarian Financing estimated the funding gap for humanitarian action in 2015 to be US$ 15 billion.

By comparison, total humanitarian aid from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development donors that same year was US$ 13.6 billion, despite an increase of 11 per cent. Filling the gap will be a huge challenge given the influx of refugees to Europe, especially as many donors, including Denmark, Germany and Sweden, are using a growing share of their aid to cover housing and other services for asylum seekers at home.

But it is not only more money that is needed. The humanitarian system also has to become more effective, efficient and transparent, according to aid experts. To address the shortcomings, the ‘Grand Bargain’ agreed to at the World Humanitarian Summit (see page 8) includes 50 commitments to improve the global humanitarian system. In exchange for more transparency and accountability from humanitarian actors, donors have among other things agreed to provide more multi-year funding.

In some ways, the Grand Bargain formalizes a process by which some donors have already begun to adjust. The Swedish aid agency Sida, for example, has been trying to put development funding streams to work in what Peter Lundberg, director of humanitarian assistance at Sida, referred to as the ‘grey zones’ between development and humanitarian aid.

“We are grappling with these issues,” says Lundberg. “We are trying to find ways to relieve some of the pressure on humanitarian budgets, taking key humanitarian principles into full consideration.”

The new Swedish five-year country strategy on Syria is a good example. It takes a holistic view, calling for coordination between development and humanitarian efforts and warning against the establishment of parallel structures. It also states that development activities must respect the humanitarian principles of neutrality and impartiality. The primary aim is to “strengthen the resilience of the Syrian population”, says Lundberg, adding that the strategy is very clear that development aid should complement but not overshadow humanitarian support.

“Development funding is expanding into the grey zone,” he says. “That is what the whole resilience debate has brought about. I see more of that coming.”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration