The move to increase direct funding to local humanitarian organizations comes in the wake of growing international attention to the funding imbalance between international and local actors, in spite of the advantages local organizations have in delivering aid in affected communities.

The IFRC’s World Disasters Report 2015, for example, concluded that the current donor regime favours international actors like United Nations (UN) agencies and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), while leaving national governments and local NGOs with a far smaller piece of the pie.

How much smaller is not entirely clear. The best available estimate of funds channelled directly to local and national humanitarian responders last year was 0.2 per cent, though it is generally agreed that this doesn’t reflect the full picture. Even Development Initiatives, the United Kingdom-based think tank that came up with the figure, says the true percentage of funding these responders actually receive is likely much higher. “It is simply our best estimate of what local and national NGOs receive directly given currently available data,” says Sophia Swithern, head of research and analysis at Development Initiatives.

She explains that the figure, which rises to 0.5 per cent for 2016, only reflects funds reported through the UN’s Financial Tracking Service, to which not all donors and organizations fully report. And it only captures what is given directly, not what comes to local and national organizations indirectly via other partners. “There is a real need for better traceability so that we can see the full picture of what these local NGOs ultimately receive and the length of the transaction chains via which they receive it,” she says.

Some donors nonetheless make their own estimates of how much humanitarian aid they give to local and national organizations. In Sweden, Sida’s own ‘conservative’ figure is 12 per cent, while one evaluation estimates that 6 per cent of Norway’s humanitarian assistance to Syria was implemented by local NGOs. The UK’s Department for International Development agrees that more funds should ultimately go to local and national first responders and it supports the 25 per cent target, but it has no estimate about how much currently goes to local organizations. Neither does Denmark.

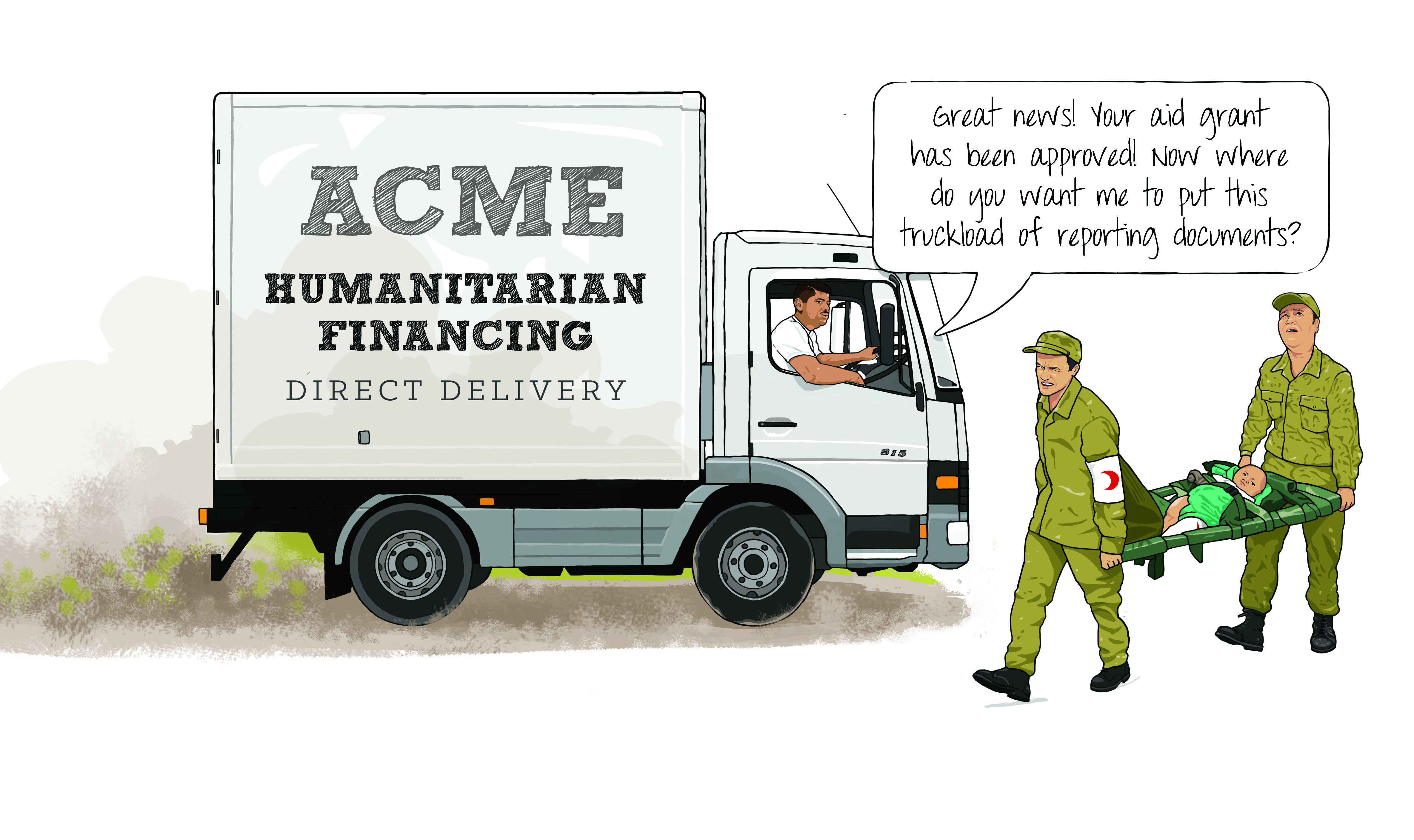

Cutting out the middleman?

The reasons for the funding imbalance are many. Strict reporting standards meant to provide basic accountability to taxpayers in donor countries and to prevent corruption or funding of organizations considered as ‘terrorist’, are almost impossible for local organizations with weaker administrative capacity to meet. As a result, donors use international agencies as middlemen, who take a percentage of the aid for administrative costs.

Critics argue this makes aid more expensive and less efficient. But what are the challenges of sending money more directly to local organizations? For donors, doing so would probably entail more agreements with smaller organizations. Some donors in recent years, however, have deliberately sought to shrink the number of recipients in their portfolios mainly to reduce the administrative burden and the fragmentation of aid. The Norwegian Foreign Ministry, for example, has an explicit goal of decreasing the number of agreements with partners from 5,500 to 4,000 over the coming year.

Sida’s Peter Lundberg, meanwhile, says it is out of the question for Sida to channel funds directly to local first responders. Sida funds that go to Red Cross Red Crescent National Societies, for example, are dispersed via the IFRC or the Swedish Red Cross. Other local organizations are funded via the Country-Based Pool Funds run by the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). “There is only one layer between us and the local NGO,” he says, referring to the OCHA funds. In the Pakistan fund, he says, 60–70 per cent of the money goes to local organizations.

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine