Beyond relief

Given the protracted nature of the Syria crisis, however, humanitarian organizations including the Turkish Red Crescent see the need to go beyond emergency relief. “In the short term, nutrition and shelter are critically important,” says Gulluoglu. “But in the middle to long term, the community centres and the things we can do to reduce the impact of this crisis on the guest communities are equally important.”

According to the needs assessment report prepared for the Sanliurfa community centre by Başak Yavçan, professor at the University of Economics and Technology in Ankara, life for refugees living in cities is in many ways even harder than for those living in the camps.

“Refugees live in crowded, single-room households, working for very low wages in aggravated conditions [and] facing discrimination,” Yavçan writes in her report, which was commissioned by the Center for Middle Eastern Strategic Studies, the IFRC and the Turkish Red Crescent.

Despite this, the city-based refugees are generally satisfied with the relative safety of their new surroundings, the free services and humanitarian aid, the hospitality of locals, the welcoming attitude of the Turkish government and the professionalism of the Turkish Red Crescent, according to the study.

But the availability of these services doesn’t mean their problems are solved. Far from it. First, there is the language barrier. While there is much cultural affinity between communities on both sides of the border, few Turks speak Arabic and few Syrians speak Turkish.

Then there are legal roadblocks. The Syrians who settle in urban areas and who do not always register as refugees in camps are generally subject to Turkey’s ‘guest law’ as opposed to national refugee laws, meaning that their rights and access to some services are reduced. One common complaint is that their children cannot attend school, which stymies their potential relationships with local children, their academic development and their ability to overcome the traumas of war, according to the report.

As the number of centres expands, the assessment of the Sanliurfa community centre offers insights into the opportunities and difficulties ahead. One potential challenge is if local residents begin to resent the services offered to refugees, given that life for locals has also deteriorated since the war in Syria began. The report recommends increased collaboration and inclusion of locals, especially children, in centre activities.

Also, if the job skills learned through the centre’s courses cannot be applied or result in few jobs, people may lose interest. The report suggests active dialogue with employers and local chambers of commerce, as well as flexible course hours, so people don’t have to drop out once they do find work.

These efforts take on greater significance given the increased pressure to stop the flow of migrants from Turkey towards Europe. Refugees and their host communities may well face the prospect of living with each other for some time to come.

Throughout the crisis, the Turkish population has been generous to people fleeing from Syria, Gulluoglu says. While international aid and donations from private individuals have played an important role, the government of Turkey has shouldered most of the costs of caring for the Syrian people living in camps.

But as the conflict drags on and refugee numbers continue to swell, will Turkish society continue to be tolerant and supportive? “The level of acceptance of Turkish society for the Syrian people is just as important as the question of the financial load,” Gulluoglu says. “The government can arrange the budget, but the level of acceptance and the level of absorbing Syrians at the community level are critical.”

Growing international operations

The Turkish Red Crescent’s international humanitarian efforts have also been increasing in recent years. When major crises occur and an international Movement response is mobilized, such as in Haiti in 2010, Nepal in 2015 and many others in between, Kizilay has been there.

Its most extensive ongoing international operation is in Gaza, where it has received significant public support for campaigns that fund food distributions, water-rehabilitation projects, support for local hospitals, agricultural projects, donation of ambulances and student scholarships, among many other things.

One of the more complex and ambitious international operations in recent years has been in Somalia, where Kizilay began working in 2011 following drought and a major food security crisis that came in the midst of protracted armed struggle between armed groups and the transitional government.

Kizilay brought in 4.6 million kilograms of food items and built a camp for 2,500 families, as well as initiating several development aid projects including a public works and engineering facility to help clean rubble, dispose of rain water and rebuild roads, among other things. It is also involved in constructing a machinery, electrical engineering and computer science school for 360 students.

These are ambitious undertakings in a country as fragile and volatile as Somalia and the efforts are not without challenges. The National Society’s emblem helped it work alongside the Somali Red Crescent Society, generally accepted by most actors, and Kizilay’s presence helped spur further action by other international humanitarian organizations.

Humanitarian crossroads

Kizilay’s international experience and its central role in the Syrian conflict and the related migration phenomenon have placed it at the intersection of some of today’s most vexing humanitarian challenges.

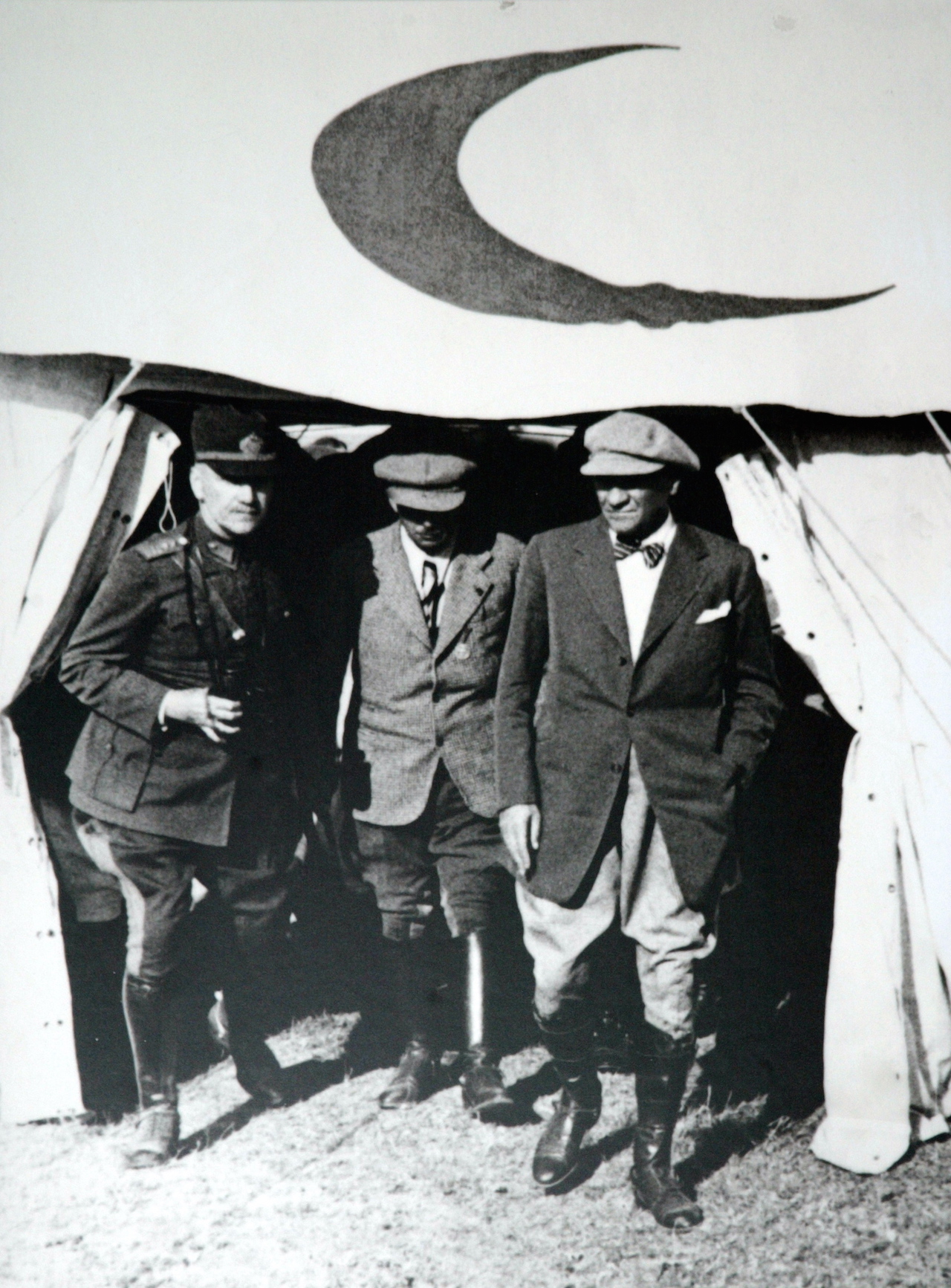

A long-time leading voice in the Movement, Kizilay belongs to both the old guard of National Societies created in Europe in the late 1800s and a vanguard of Red Crescent societies increasingly making their mark in an aid world that has been historically dominated by Europe and the West. That is starting to change and Red Crescent societies are part of that process, playing a larger role in international humanitarian operations and leading relief efforts on the front lines of many of today’s emergencies.

“Turkey was always a bridge country: between East and West; between North and South; between Africa and Europe,” says Gulluoglu.

As leading humanitarian organizations meet in Istanbul for the World Humanitarian Summit in May, the Movement’s oldest Red Crescent society is in a position to bring all its experience to bear as humanitarians collectively re-imagine how to develop more sustainable and effective responses to the world’s most intractable problems.

“We have to use humanitarian aid resources efficiently and effectively,” says Akar, when asked about his hopes for the summit’s outcomes. “We are providing help to millions of people as a humanitarian organization, but there are more people in need. This means we have to find new resources and also use current resources more effectively.

“We must push and mobilize our governments for both support and protection of our work. Governments should understand that we are impartial humanitarian aid workers,” he says. “If [this understanding] is achieved, we will then be able to provide more help to places such as Gaza, Somalia and Iraq. I hope that the summit will produce a new approach and more coordinated road map of humanitarian aid.”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration